2013

Jul

31

How Moral Dilemmas Develop Your Character(s)

Yes, your personal character, too, but I'm really referring to the characters you write.

Everyone loves a good villain, from Simon Legree to Darth Vader. But only slightly less appealing is a juicy moral dilemma. Some of them are easy, like, "Should I go back to my daughter or blow up this damned asteroid and save the planet?" Others are more delicate. There is one in particular that has left me dangling, literally, for decades:

Once upon a time, in the days when there were still isolated tribes in Africa, there was a Christian missionary and his wife. The missionary had made great progress, having successfully constructed a church building and converted several members of the tribe, including the chief, to Christianity. Naturally, he gave the credit to God, but he also recognized that God was aided by the missionary's respect and acceptance of both the people and their culture.

One aspect of that culture, however, gave him some problems. It was tradition that when a man's son or daughter reached 12 years of age, he would select a close friend of the opposite sex to introduce that offspring to the joy of carnal delights. To be so chosen was a great honor, and to decline the most grievous of insults.

You guessed it. The chief's daughter came of age, and so he chose to bestow the greatest possible honor -- the deflowering of the chief's daughter -- to the most honored guest -- the missionary.

Therein was the poor fellow's dilemma. Should he betray his marriage vows and perhaps the trust of his wife, or should he betray the trust of the tribe and risk destroying all that had been created by sorely insulting both the chief and his daughter?

To the best of my memory, this is a true story, and I don't know how it turned out. I have wavered back and forth on this for some time, and now I'm leaning toward the conclusion that he should. But for the sake of this article, it doesn't matter which he chooses.

To the best of my memory, this is a true story, and I don't know how it turned out. I have wavered back and forth on this for some time, and now I'm leaning toward the conclusion that he should. But for the sake of this article, it doesn't matter which he chooses.

Just as it probably is for your characters immersed in their own moral dilemmas. Pick the choice that furthers the plot, because the actual choice has very little meat to it.

Now it is necessary that I justify that statement.

It's about the why, not the what

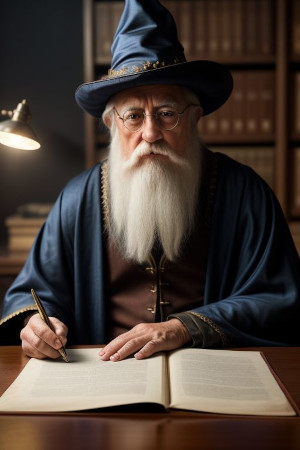

One of the great icons in developmental psychology is Lawrence Kohlberg. Kohlberg has his detractors, of course, but I've worked with a lot of kids and frankly Kohlberg is right on. The studies for which he is best known focus on the development of moral reasoning, and consisted of questions like the Heinz Dilemma: is it right or wrong for a poor man to steal an expensive drug to save is dying wife?

Kohlberg could care less rather people said yes or no. What he wanted to understand is why they made that particular decision. And in analyzing those results is where he came up with what are now known as Kohlberg's Stages of Moral Development. If you're interested in more, I found a good discussion here, but in fewer words, he identified six levels of development, and a particular kind of reasoning that goes along with each.

Let me throw in that there was the later addition of a stage zero (which I will mention because it suits so many villains), and speculation about a stage seven. However, given the small number of people he could find that satisfied stage six, he hasn't tried to prove anything beyond that.

Where does your character fit in?

You don't need to get into the details of concrete and formal operational thought, or of pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional reasoning. Leave all that to the psychologists. I learned it when I was doing adventure education. It's enough to know how the six levels think. Let's go over them one by one, and decide what that missionary should do.

I'll not try to explain in technical details what those levels are. It seems that as writers, we would rather have a peek into the minds of those involved.

Stage 0: Good is what I like

The missionary could decide to do it because, hell, it would feel good and an opportunity like that comes once in a lifetime. Or he could decide not to because being an A++ missionary would go good on his resume. Note that neither motive seems appropriate for a missionary. They're good motives for villains, though.

Stage 1: Obedience and punishment orientation

He could decide to do it, because if he didn't, the tribe might fall away from the church, and the Bible says not to put a stumbling block before your brother, and no one wants to disobey God. Or he might decide not to because the Bible says to be faithful in marriage and no one wants to disobey God.

Stage 2: Naively egoistic orientation

The missionary could decide to do it because that would endear him more to the tribe and make his ministry more successful, or he could decide not to because if he did, his wife would get really pissed off and make his life miserable.

Stage 3: Good-boy/good-girl orientation

He could decide to do it because a good missionary always does what it takes to further the reach of the Gospel, or he could decide not to because a good Christian never cheats on his wife.

Stage 4: Authority and social-order-maintaining orientation

He could decide to because it is long-standing tradition among the tribe and it would be unethical to do anything that might disrupt the society, or he could decide not to because the sanctity of marriage is fundamental and his own society would crumble if people went around cheating.

Stage 5: Social contract orientation

He could decide to do it because he has a responsible relationship with the tribe and they are depending on him to do what they see as the right thing, or he could decide not to because he pledged wedding vows to his wife and has to remain faithful to that obligation.

Stage 6: Universal moral principle

The missionary could decide to do it because furthering the gospel is the greater good, or he could decide not to because not being true to his ideals threatens everything he is trying to accomplish.

I understand that it is sometimes difficult to tell the difference between some of the stages, but they are there. If you find yourself enthused about the subject, go back and read some of Jean Piaget, since it is his work upon which Kohlberg's is founded, and understanding the cognitive processes underneath is helpful. What might be of more help is to read over the examples a few times to get the feel, and maybe look up examples elsewhere on the internet.

How does your character grow?

Kohlberg was interested in moral development, and writers are interested in character development, so we're all in agreement. One of the principles Kohlberg established is that development is always sequential, that no one ever skips a stage. Therein lies gold. Early on, your character is struggling with a moral problem at one level, and as he grows, the readers watch his reasoning process shift to something more mature.

Note that most modern societies as a whole operate at Stage 4 (it's the law!), which produces some interesting conflicts when that society confronts someone operating at a higher level. Consider Gandhi.

And there is an added bonus: many such decisions are made with the person deluding himself into believing he is following a higher ideal, when in truth the motivation is something more base. What a good time to throw in some justification and rationalization!

In my as yet unpublished novel A Hierarchy of Gods, the protagonist Lesley Kellerman is constantly fretting over doing the right thing, breaking what he understands as both social and moral laws for a higher goal. In the end, he achieves some understanding of Stage 6 as he tells the vile Canard, "What is right is what you do in love."

When your next character has an important moral decision to make, especially if it's one of those juicy dilemmas, pay special attention to how she makes it.

Comments

There are no comments for this post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.