2014

Apr

10

How the Ph.D. Lost its Luster

Anyone who's known me for a while would probably assume, as I always have, that eventually I'd go back and get a Ph.D. After all, it's the shining pinnacle of scientific geekiness, isn't it, and there are have been few science fanatics geekier than I. I designed my first digital computer when I was 12. Now that was back before integrated circuits, so it took some real work. I invented integral calculus in 7th grade because I ran into a math problem I couldn't solve. I invented object-oriented programming sometime later to solve a similar problem. It didn't matter that those things had already been invented; I didn't know. I was just taking advantage of my inner geek to get something done. Naturally, a geek like me would go for a Ph.D.

But then came that moment a little over a year ago that applied some tarnish to that shine. Actually, it goes back farther than that, back to the time when I could call myself young without using too much imagination. I was watching a nature program on television. In it, a group of baboons had found themselves a tiny hill and were fighting over who got to stand at the top of it. It sure was important to them. They would gang up on the fellow who had made it to the top and pull him down only so another could take his place and repeat the cycle. And this was no game; it was serious business. Each one of them just HAD to be the baboon at the top of the hill and it didn't matter who got hurt in the process.

My first thought, of course, was, "Congress!" That's probably where the claim came from that a group of baboons is called a congress. Actually, primate biologists call a group of baboons a "tribe," but the term seems to fit, doesn't it? It was funny at first, but it didn't take me long to realize that this inherent baboon-ness pervades human society. Our economic system thrives on it: a zillion petty companies trying to tear each other down so that each one can have its 30 seconds at the top of the hill.

My first thought, of course, was, "Congress!" That's probably where the claim came from that a group of baboons is called a congress. Actually, primate biologists call a group of baboons a "tribe," but the term seems to fit, doesn't it? It was funny at first, but it didn't take me long to realize that this inherent baboon-ness pervades human society. Our economic system thrives on it: a zillion petty companies trying to tear each other down so that each one can have its 30 seconds at the top of the hill.

Oh, we stopped playing literal King of the Hill, when we were kids, didn't we? Now that we are "grown up" we wouldn't be be caught dead fighting over a real hill, so we use the intelligence with which God or nature has gifted us to invent virtual hills to fight over. We call them things like "preferred stocks" and "investment banking." Get to the top of the hill at all costs, and it doesn't matter what other baboons you maim to get there. Furthermore, we have applied our intelligence to inventing plausible explanations as to why this innate primate behavior is somehow "civilized."

The truth is, it upsets me greatly that I belong to such a species. If you read my science fiction, you know that I create advanced species that are above all this. In The Saga of Banak-Zuur, they are called non-competitive. They don't fight each other for supremacy; they cooperate for the common good, and for that reason are far ahead of us. Most never invented money because they never saw a reason to deny resources to others, and many never even invented laws. Those are trappings we hang onto as crutches to feed our illusion of civilization. I suppose I wish we could be like those alien races I invent. I often wonder where we would be if we hadn't pissed away 1000 years having the Dark Ages like a bunch of, well, baboons. We could have warp drive by now, cures for every disease, peace on Earth. But to hell with that, because I see another hill!

I'm not alone in this dream. The future world of Star Trek, for one, is largely utopian. They've given up money, but still have laws. Maybe they'll outgrow those someday? We can only hope.

I've had a glimpse of what such a world can be like because I've worked on some crackerjack development teams. ASI is a perfect example. Tom was the database guru; Tony the Delphi components wiz. I was the object-oriented architect. Janet was sort of the new kid on the block, but learning fast. We knew that the company existed in a larger arena of competition, be we were rather insulated from that. We worked together smoothly, not competing with each other, but cooperating to the best of our abilities to create something new. It was awesome! That's the way it should be. I've also worked in companies full of internal politics, and those types run like an engine with sand in the oil. When you're not wasting your energy fighting each other, you have more to invest in what you're trying to accomplish.

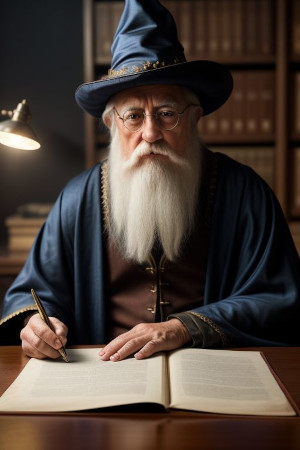

And all this is why I loved academia so much. It was a shelter from the constant reminder that I'm living in a world of primates. The philosophers only cared about teaching philosophy. The English professors only cared about teaching grammar and composition. The physics professors only cared about teaching physics. It was a world where a geek could immerse himself in science and momentarily forget about the cutthroat baboons outside. I tried to hang onto the delusion that graduate school would be that way. I knew about the importance of funding, but still believed that it was a necessary evil on the way to research.

I got some hints to the contrary my first summer at Pitt, but I did my best to ignore them. It was at that time I was attempting a condensation synthesis using pyridine derivatives as a catalyst. I found a paper on the subject that said, basically, "We tried this, this, and this, and nothing worked." I was ecstatic! That was the most awesome paper I had ever read! It could potentially save me months of wasted time trying those same things over again.

It was months later at a seminar that I mentioned that paper to someone. His reaction was the beginning of the end. "You don't get funding based on negative results, and you don't want to publish stuff that'll help your competition too much."

It was like a cold knife into my soul.

Baboons!

Even here, I couldn't escape them. I kept my eyes a little more open after that. Yes, you have to be careful what you publish. It has to make your team (and perhaps your collaborators) look good without unduly helping out competing teams. Research results are sometimes hidden if it deemed that publishing will help out someone else more than it does you. Research results — even important ones — may be buried if they might make too many waves and cause funding sources to take a more critical look at you. You have to make it look like your research fits into one of the hot categories that it is currently popular to fund. On top of this, we need so much funding because science has become — I hate to say it, but it's true — big business.

Even here, I couldn't escape them. I kept my eyes a little more open after that. Yes, you have to be careful what you publish. It has to make your team (and perhaps your collaborators) look good without unduly helping out competing teams. Research results are sometimes hidden if it deemed that publishing will help out someone else more than it does you. Research results — even important ones — may be buried if they might make too many waves and cause funding sources to take a more critical look at you. You have to make it look like your research fits into one of the hot categories that it is currently popular to fund. On top of this, we need so much funding because science has become — I hate to say it, but it's true — big business.

Everything is big business, because we don't do anything that doesn't lead to the top of the hill.

After that, my heart sort of left it. You know how they say that babies are born scientists, exploring every detail of the world, until school drums it out of them? Well, it's true. It's true in grad school, too. I felt the love of science being drummed out of me. Funding isn't a necessary evil on the way to research; research is a necessary evil on the way to funding. My love of science was being squeezed to death under a mass of baboons, and I couldn't bear to watch that happen.

If you haven't seen The Fifth Element, you really should. Near the beginning, one of the Mondoshawans says, "Time not important. Only life important." It's depressing how we can see things so clearly when it comes to putting them into plots, but less so when it comes to our primate existence. Science not important. Only life important. You probably never thought you'd hear me say that, but it's true. Science is only important to the extent that we use it to help each other. If it's just a quick trip to the top of the hill for 30 seconds of fame, I have no use for it. It's a game I don't want to play.

So I had to question what I really wanted with a Ph.D. It was a ticket into a world that looked great from the outside but was full of rust on the inside. My God! Will we ever evolve? I couldn't see myself having to make science second fiddle to funding proposals and publications. That's not what the love of science really is.

Let me teach it. That way, not only can you experience the love of it, but you get to share it with others along the way. And where does a Ph.D. fit into that? For one, if you want to teach college, you almost have to have one, despite the fact that a Ph.D. in no way prepares a person to teach. Not one little iota. Let's face it, there are some tenured professors out there who are great at managing a lab, but suck in front of a class. But that doesn't matter. They have their credentials, that brings prestige to the university, and that brings ... funding.

I'm sorry. I just can't see myself scrambling around in that crowd for the top of some metaphorical hill. I want to do something REAL.

Comments

There are no comments for this post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.