2014

Jun

23

Introduction to Trarsani 4: Tense, Aspect, and Mood

How to think about languages

This is the part that I dreaded writing because I wasn't sure how to approach it. But what it boils down to is that the first step is not mine, but yours. Unlearn everything you know about English. When we use language, we communicate all manner of notions about ownership, causation, time frame, direction, and so forth. English uses prepositions and word order to do that, but there are other systems. There are other systems among human languages, so it follows that there are other systems among non-human languages. Trarsani does not have prepositions in the same sense as we do, and word order doesn't do nearly the same thing as it does in English.

You probably know that when you translate between languages, you can't just swap out words. I remember when I was a kid, I think in history or geography class, we learned about the Pennsylvania Dutch. Supposedly, some of them decided to convert to English and did it by swapping Dutch words for English ones, coming up with some wild expressions. Two that I remember are, "Close the gate wide open," and "Throw your father down the stairs his hat." English words with Dutch sentence structure makes for some interesting results, and here's the rub. On the scale of languages, English and Dutch are nearly the same. Try that with English and Mandarin!

So forget about prepositions and word order. Forget about subordinate conjunctions. Forget about gerunds and participles and adverbial phrases. We'll have to learn a new way of doing things. I've split these matters up into six categories: tense, aspect, mood, case, voice, and some miscellanea that don't sense in English. These all have definitions, but even so, they tend to blur together. Especially tense and aspect, which both have to do with time. When we say in English something like "would have been," we are combining tense, aspect, and mood. So let's start taking them back apart, beginning with those three. We'll begin with the one that is probably most familiar to most of you: tense.

Tense: Particles about when it happens

Tense, as I'm sure you know marks location in time: past, present, or future.

| Particle | Roman transcription | Meaning | English example |

|---|---|---|---|

|

present tense (default) | say | |

|

po- | past tense | said |

|

zo- | future tense | will say |

So, said in Trarsani is po-dilai, and will say is zo-dilai. That's easy enough, right? Wrong. Naturally, it's a little more complicated than that. These prefix particles can be combined: po-po- means that as of sometime in the past, it was already in the past, similar to had been, and zo-po- means that as of sometime in the future, it was in the past, such as will have been. The English equivalents are not exact, however, as they may contain elements of aspect, suggesting that whatever we are talking about was actually completed as of sometime in the past or future. These Trarsani expressions do not contain that notion.

You might recall from last time that I said Trarsani is more fluid than English. There is nothing to prevent attaching one of these particles to a stative (adjectival) verb: apple po-irai (the apple was red) or even to a noun: po-apple (whatever it is now, it was an apple). Assuming you're not still one, you are a po-child, a child in the past tense. Actually, we have this in English: ex-girlfriend. But for virtually all of the particles that follow, we don't.

Aspect: Particles about a relationship with time

Now here is where it starts to get scary (there is an inchoative aspect in that sentence). Aspects also indicate a relationship with time, but instead of where in time, it's how it relates to time. Whether it is beginning, ending, or completed. Whether it is continuous or progressing. Whether it happens in an instant, continuously, regularly, or over and over.

Aspects are sometimes classified as either perfective (finished) or imperfective (not finished), but we'll let that distinction slide. The "perfective" in the table below is slightly different. It is easy to identity them in a sentence, because they all rhyme.

| Particle | Roman transcription | Meaning | English example |

|---|---|---|---|

|

too- | momentane aspect: It happens all at once | It popped! |

|

doo- | inchoative aspect: It is beginning | It's starting to rain. |

|

zoo- | cessative aspect: It is ending | I'm done fixing supper. |

|

thoo- | sequitive aspect: It happens at the proper time | |

|

koo- | durative continuous aspect: It is ongoing | I'm still waiting |

|

poo- | durative progressive aspect: It is ongoing and progressing | It's coming along fine. |

|

loo- | habitual aspect: It happens regularly (as a habit) | I speak Trarsani |

|

roo- | iterative aspect: It happens over and over | I keep stubbing my toe. |

|

shoo- | perfective aspect: It is complete |

I don't have (as of the time of this writing) an English example of the sequitive aspect, but I hope to come up with one. It might be difficult, however, since I had to invent the term sequitive. There are human cultures (native Americans?) who have this notion in their thinking, but we Europeans aren't really among them. At one point in A Hierarchy of Gods, Ritee says, "All is as it should be." She says that with this sequitive aspect in mind, i.e., this is when it was supposed to happen. There is an argument for the sequitive being a tense instead of an aspect, but as I don't know of any equivalent among human languages, I just made my best guess.

When doo- and zoo- are applied to places and times, they often take a slightly different role, being interpreted as starting-at and stopping-at, respectively. They translate most often as from and to. Fei doo-Cincinnati zoo-Columbus po-zai (I starting-(at)-Cincinnati stopping-(at)-Columbus did-go), or I went from Cincinnati to Columbus. However, there are cases where they might mean the start or end of a time or place. Lent, for example, has a start and end. It is usually apparent from the context, and is one of the few cases where there is some ambiguity in Trarsani. Applying doo- and zoo- to a stative verb indicates that the subject is entering or leaving that state. Apple doo-irai.

Shoo-, the perfective aspect, I think is hard to explain. It's hard to explain perfectives in English, but grammarians try all the time anyway. It's sometimes described as viewing the action as a "simple whole." If it's a simple whole, it has no fine structure with respect to time, so you can't say it's ongoing or talk about its beginning and end. That's why I described it as "complete." It differs from too-, the momentane aspect, in that the latter happens at a point in time, and a perfective not necessarily so.

I was going to go over some more examples here, but I suspect that the ones I show in the table are enough for now. Where you really need the examples is after we discuss mood, as they all work together to communicate concepts that we express in other ways. And then there will be more when we throw in case next time. So let's move on.

Mood: Particles about how the speaker feels about the subject

Grammatical mood is rather hard to define. We learn about the subjunctive mood in school, but that's only the tip of the iceberg. Mood is everywhere. In general, it expresses the speakers attitude toward what is happening, but then we have to ask exactly what attitude means. Mood expresses ideas of causality, being conditional, subjective vs. objective, potentially, obligation, and more.

Moods are often subdivided into realis (actual, real things) and irrealis (hypothetical, wished for, asked for, etc.) But as with aspect, we'll not worry about that level of distinction. They don't all rhyme as the aspects do, but the common ones are simple, short syllables, and many do rhyme.

Are you ready?

| Particle | Roman transcription | Meaning | English example |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nem- | indicative/demonstrative mood: plain statement of fact. | The oven is hot. |

|

shek- | subjunctive mood: the hypothetical | If I were a rich man... |

|

shef- | causative mood: a condition for something else | If you smash your finger, it will hurt. |

|

nesh- | optative mood: something that is hoped for | I expect that your mother will spank you. |

|

neth- | desiderative mood: something that is desired. | I want to be able to play the piano. |

|

koi- | imperative/precative mood: a request | Can you help me? |

|

tho- | jussive mood: an exhortation | You should help me. |

|

ned- | tentative mood: something there is a little doubt about | I'm sure it will work. |

|

nin- | inferential mood: when something is implied | II hear that she has finished |

|

shee- | interrogative mood: asking a question | Are you coming |

|

nei- | conditional mood: dependent on something else | ... then I'll come with you. |

|

kei- | potential mood (1): the ability for it to happen | I can do this! |

|

dei- | potential mood (2): the possibility for it to happen | I might do this |

|

sei- | obligative mood: indicating necessity | I have to go to work now. |

|

tei- | permissive mood: allowed to do something | You may play on the porch. |

|

yan- | volitive mood: indicating a will to do. | I'm going to kick your butt. |

You're thinking, "Oh, my God! I have to learn all of those?"

The good news is that you already have. You've learned them in English, and English is quite a bit harder because instead of being simple, unambiguous, single-syllable particles, they're built up of varied and seemingly random combinations of auxiliary verbs, adverbs, prepositions and other words. Get used to it and you'll like it.

The examples above might give you some idea of what they all do, but let's take a moment to highlight the details.

The Details

nem-

The indicative/demonstrative mood just states a fact, ma'am, and most of the examples I've given up until this point are in this mood. Most sentences are. For that reason, you rarely see nem- as sentences (and the words put into them) are demonstrative by default. However, it does sometimes appear as an emphatic to clarify that a statement is true. Apple nem-irai. "The apple is red, and that's a fact!"

shek- vs. shef-

It is easy to confuse the subjunctive and causative moods in Trarsani, because you probably confuse them in English. It's even more confusing because we use the causative mood in what we call conditional clauses, and conditional refers to the other end of the sentence, not the cause.

Let's try to do this. The subjective is something hypothetical. You're letting your mind wander or just being silly. "If we had a key we could walk out of this jail." The causative is more real, something that can, and maybe will, happen. Something that something else depends on. It boils down to a spectrum from impossible to the certain.

- Subjunctive: If he be dead, I shall be a happy man.

You don't think he's dead, and it's not a very realistic prospect. This is a desire. An "if only". Notice the use of the subjunctive form be, falling into disfavor in English, but which I wholeheartedly endorse.

- Causative: If he is dead, he won't be able to testify.

You really think the hit man got him, a very real possibility.

- A stronger causative: If you take LSD, you will hallucinate. This is certain!

As we can see, the structure of these sentences is exactly the same, the old if-then structure. That is why they are so easy to confuse. We can go even farther the other direction, and propose a subjunctive that is totally impossible and doesn't even include the word if: "May the bird of paradise fly up your nose!" Completely hypothetical. It's never going to happen. This is a hypothetical that has no causative or conditional attached.

Let's try an example in Trarsani, again using the Roman alphabet for clarity.

"I would eat if I had food."

“Fei bentee shek-shef-krai nei-brai” ("I food if-if-have conditional-eat.)

The shek-shef- transliterates as if-if- because we use if for both the subjunctive and causative aspects. Here, the speaker is saying that having the food is both hypothetical (apparently he has none, and no prospects) and causative (if he had any it would lead to him eating.) Linguists speculate that shek- and shef- evolved from a common root word and differentiated as people came to want more precision. In casual speech, though, it is unlikely that the speaker would use both of them, and likely just pick one or the other depending on what he wanted to emphasize. the shek-shef- combination is another case of fusion (see last lesson). Keep an eye open for those.

The nei- particle gives us the "then" part of the sentence.

nesh- vs neth-

Nesh- and neth- are two other possibly genetically related particles that can easily be confused, especially by English speakers. We have this annoying habit of using hope to mean wish. Hope originally referred to something that you fully expect to happen, that you are looking forward to. "Oh. Getting married tomorrow? I bet you're hoping for your wedding night!" That is the meaning of nesh-, an expectation. Neth- is a wish or desire. "Gee, I wish I could find a girlfriend!" Note that I'll be using hope to mean wish, and if I mean, "hope," I'll say, "expect."

This is a good place to introduce examples of how a particular particle can be applied to various words in a sentence. Consider "I hope Betty comes tomorrow." Let's remember that this hope is more along the lines of a wish, so we use neth-. Depending on where we put stress, it can mean, "I hope Betty comes tomorrow," "I hope Betty comes tomorrow," "I hope Betty comes tomorrow," and so on. Let's do this in Trarsani.

| Romanized Trarsani | English equivalent |

|---|---|

| Betty toi-arthee vandai | Betty is coming tomorrow |

| neth-Betty toi-arthee vandai | (It is hoped) Betty is coming tomorrow |

| Betty neth-toi-arthee vandai | (It is hoped) Betty is coming tomorrow |

| Betty toi-arthee neth-vandai | (It is hoped) Betty is coming tomorrow |

You can see that there is a rough equivalence between the particle (neth- in this case) and the emphasis in English. Therefore, you might wonder if it wouldn't be easier just to use emphasis as we do. It might, but it's not as good. So let's get to something really cool about Trarsani that you can't really do in English.

What would you say about, "nesh-Betty neth-toi-arthee vandai"? The optative mood is applied to Betty and the desiderative mood to tomorrow. This means, essentially, "I'm expecting Betty to come and I'm wishing it's tomorrow." That's a lot to say with three words, along with their associated particles. It is possible in Trarsani to put thoughts together in ways that you haven't seen before. We can't use emphasis to shade the meaning, because there would be two kinds of shading.

Now breathe. This is a moment to take a break from cramming facts into your head and instead ponder about what it all means. We've taken a little three-word thought, Betty comes tomorrow, and adjusted its meaning quite a bit with two little particles instead of adding three more verbs and building a compound sentence around it. The person who grew up on verb-centered English might ask, "Well, who's doing the expecting and hoping?" You can see that I made it the speaker in the rough translation in the previous paragraph, and in the table above used the passive voice to avoid saying who. Neither of these is actually right. The Trarsani sentence doesn't say anything about who is doing the hoping, and it's not passive.

Now breathe. This is a moment to take a break from cramming facts into your head and instead ponder about what it all means. We've taken a little three-word thought, Betty comes tomorrow, and adjusted its meaning quite a bit with two little particles instead of adding three more verbs and building a compound sentence around it. The person who grew up on verb-centered English might ask, "Well, who's doing the expecting and hoping?" You can see that I made it the speaker in the rough translation in the previous paragraph, and in the table above used the passive voice to avoid saying who. Neither of these is actually right. The Trarsani sentence doesn't say anything about who is doing the hoping, and it's not passive.

In fact, I've tried variants like "Betty, expectedly, comes hopefully tomorrow," but that's not formally correct because expectedly and hopefully, being adverbs, must apply to the verb and so there is no way to be sure which nouns they go with. If we make them adjectives, as in, "Expected Betty comes wishful tomorrow," we have to realize that tomorrow is not wishful. How about, "Expected Betty comes wished tomorrow?" Now, that's just weird. I don't think a literal translation to English is possible. Take this breather to try to get into the groove of Trarsani thinking.

If you're curious enough to wonder about the difficulties of translation in general, check out dynamic and formal equivalence. Often you can translate the words but doing so misses the meaning, or you can try to translate the meaning, but can't use matching words to do it. This is why I say from time to time that, ideally, everything should be read in the language in which it was written. (Except Kant, of course!) Unfortunately, I don't know every language.

However, it is possible to translate, "I'm expecting Betty to come and I'm hoping it's tomorrow" almost literally into Trarsani. Using English words to highlight the sentence structure. "I Betty at-tomorrow come expect and (u-u-u) I it at-tomorrow hope." However, no Trarsani would ever say it that way unless delirious.

koi- and tho-

We've talked about koi- before. As a particle attached to a verb, it turns it into a request. "Please hold this" or just "Hold this." becomes "Ka dree koi-finai." (You this please-hold.) The tho- particles turns it into a stronger request with a subjunctive tone: "Ka dree tho-finai." (You this really-should-hold.)

The precative and jussive moods bring up some differences in psychology that you should be aware of. We use please to be polite, but the Trarsani have no concept of politeness, except for people like Ritee who study races like humans had have to learn about it. The precative in Trarsani, therefore, has no notion of politeness attached to it; it is simply a marker to distinguish a statement (You are holding this) from a request (Please hold this). Likewise, if calling it an imperative mood, we must bear in mind that there is no concept among the Trarsani of giving orders. In Trarsani, the precative and imperative moods blend into one.

The jussive is different from human experience in the same way. Often, the jussive among humans contains a veiled threat: "You would do well not to offend the king." The Trarsani have no concept of either offense nor personal threats. Nor is there anything like begging. If the poor guy a few paragraphs up needed food, he wouldn't even have to ask. All he would have to do is say he was hungry. In Trarsani, the jussive tho- merely suggests that failure to act may have undesirable natural consequences. "You really should take your hand out of the blender."

This is a good time to point out words like offend, hate, war, and greed don't translate at all into Trarsani because those concepts don't even exist. Likewise, I've tried to point out how leekee doesn't translate well as love, but it's about the closest word we have. Difference in fundamental concepts and world-views can be a big problem in translating between species.

ned- vs nin-

Again, we have two particles that are similar. Both express a degree of uncertainty, suggesting that something is true but not confirmed. ned-, the tentative mood, emphasizes that there is a shadow of a doubt. nin-, the inferential mood, emphasizes that the fact is a conclusion, "inferred," or reported by a third party. Beginners can probably use them interchangeably without provoking a disaster.

Lets look at some examples.

| Romanized Trarsani | English equivalent |

|---|---|

| Ben lavolai | Ben is sick. |

| ned-Ben lavolai | Ben is sick, but there's a chance it's not Ben. |

| Ben ned-lavolai | Ben is sick, but there's a chance he's not. |

| nin-Ben lavolai | I understand it is Ben who is sick. |

| Ben nin-lavolai | Ben is sick, I understand |

| ned-Ben nin-lavolai | I understand that someone is sick, probably Ben but possibly someone else. |

shee-

We touched upon shee- with our discussion of the shee- words last time and the abbreviated sentence structure that goes with them. Sheevo, sheelo, sheezee, and so forth. However, shee can also be used as a particle to add an interrogative.

| Romanized Trarsani | English equivalent |

|---|---|

| shee-Ben lavolai | Is it Ben who is sick? |

| Ben shee-lavolai | What's with Ben? Is he sick? |

In the first example here, the English uses the reflexive pronoun who to reference back to Ben. Trarsani doesn't require that sort of construct, as a question can be applied to any part of a sentence. You will only rarely see reflexive pronouns in Trarsani.

Last time, we talked about the Eek- sentence modifier that acts like a question mark. That remains true. But eek questions the verity of an entire statement without regard to any part of it. the shee- particle allows much greater control.

nei-

We mentioned nei- above as the "then" part of a conditional sentence, meaning that the word to which it is attached is conditional on something else. Often, the rest of the sentence will tell you what the conditions are, but not necessarily. You could say, "Fei nei-zo-vandai," meaning, "I will come, conditionally." If you can get away from work, if you can afford the ticket, if ... whatever. You're just not specifying. "Call me!" "I (nei) will!"

kei-, dei-, sei-, tei-, and yan-

We wrap up our details with the particles that correspond to English auxiliary verbs, or "helper" verbs as you might have learned them: can, might, must, may, will. Technically, these are modal verbs, as they adjust the mood of another verb.

Since these all work in the same way as the English equivalents, there is not much to say about them other two minor points. There seems some disagreement among human linguists whether to you the term potential to mean ability or possibility, so I've used it for both, but on separate lines to make it clear that they are different. The other is that yan- refers to intent. In English we use will for more than one thing, such as your free will (intent) and as a future tense indicator. yan- has nothing to say about tense, just as zo- (future) has nothing to say about mood. Beware of keeping those thoughts separate.

Practice using particles

OK, folks! Now that we have tense, aspect, and mood under our belts, let's practice putting all of that together. I know you don't have all of the vocabulary (I have to look things up, myself), but try to figure out how you would put a Trarsani sentence together given the English I'll hit you with.

"When you stop crying, I will start."

First of all, let's take a look at what the sentence is not saying, because there are some misleading words. The word will has nothing to do with either intent or that it takes place sometime in the future. It's likely in the near future, but it could be right now. The word when is normally used in association with time, but there is no specific time mentioned. So this sentence really says nothing about tense.

Now what does the sentence way? Starting with when, we see that it does refer to time, but what it means is that the time you stop crying is the same time that I start crying. It's a time relationship, and therefore an aspect. We have the ending of one crying (cessative aspect) correlated with the beginning of another crying (inchoative aspect). The second major factor is the dependency between the two, i.e., that my starting crying is dependent on your stopping. This is a causal-conditional mood relationship.

So now we know that we need the particles doo- and zoo- for the aspect relationship and shef- and nei- for the causal relationship. Putting all this together, remembering the rules for sentence structure:

"Fei ka shef-zoo-nozalai nei-doo-nozalai."

Or transliterated: "I (you causative-stop-cry) conditional-start-cry." In cases like this, the final verb can be omitted, leaving only the particles, because we know the sentence has to end with a verb and we can assume that it is the same one as used earlier, just as we do in English. Fei ka shef-zoo-nozalai nei-doo.

"I have been sad ever since Sally died."

Here we have another causative-conditional pair. These are more common than you think; they don't all contain the if-then construct. One might assume that it is Sally's death that caused the sadness, but this sentence isn't really saying that. It could have been something else that happened at the same time. So we want to make the time of Sally's death the causative. To do this, we have to inject ga-, the genitive (possessive) case marker. There are a couple of ways to do this. We can use two genitives to show ownership: the time of the death of Sally, or just one: the time when Sally died. Let's take the latter because it's more interesting. However, note first that the second phrase doesn't contain a possessive in English. This is common. Cases and prepositions are often used differently in different languages, and in Trarsani, this is a genitive: (Sally died)'s time.

We apply shef- to the time because that's the cause. the possessive particle ga- actually goes to the entire phrase about Sally dying, but we attach it to Sally because that is the first word in it. We use po- because it is necessary that the death is in the past. As before, we attach nei- to the final verb to show it to be the conditional, but since this is a continuous sadness, we also use koo- for the durative continuous aspect. (Whew! Got all that?) So we have:

"Fei shef-zanat ga-Sally po-zhizhonai nei-koo-butai."

Or transliterated, "I causative-time of (Sally did-die) conditional-continuous-sad."

"I understand Trarsani well enough to translate it."

I'm going to switch things around on this one and give you the Trarsani translation first, and then pick it apart.

Fei za-Trarsanzik shef-zeeo-olo toilai dree nei-kei-zhotonai.

Or transliterated "I direct-object-Trarsanzik cause-sufficient-well understand it conditional-can-translate." (Well, that sentence makes absolutely no sense with English words. Shades of the Pennsylvania Dutch, huh?) But we can do it!

Still again, we have a causal-conditional relationship, and let's take about the clause that's the cause first. (Fei) za-Trarsanzik shef-zeeo-olo toilai. This is one of those cases where there is a second subject (fei), which is understood. za- is the direct object marker, because Trarsanzik is what is being understood. Without the shef- and zeeo-, this clause translates to I understand Trarsani well. The direct object marker can be omitted if the clause is rearranged so that Trarsanzik appears just before tolai, because a noun in that position is assumed to be the direct object.

The words olo and zeeo are qualifiers. We'll learn more about those in Part 6, but for now think of them as adverbs. It's safe to call them adverbials, I suppose, but I have reservations about calling them adverbs. Olo translates fine as "well". Zeeo literally means a sufficient quantity (it's a counting qualifier, or quantifier), and it makes sense to translate it as enough. So zeeo-olo almost literally means well enough. Since the shef- causative particle is attached directly to the phrase, it is the well enough that is the cause for the latter clause in the sentence, not just the understanding.

What if we had put the shef- on toilai? A Trarsani would probably understand what you meant after shaking her head and blinking a few times. You just said that your understanding of Trarsani enables you to translate it. However, you also said that you understand it well enough, but not enough for what. I suppose this is the Trarsani equivalent of a dangling modifier.

Dree is the version of it used for something near to the speaker, and is the default form used reflexively as here unless there is good reason to use another one. Dree refers back to the noun Trarsanzik, and is the direct object of the final verb, but does not need the za- particle because of its placement immediately in front of the verb phrase. We already know about nei-, so the only new thing here is kei-, which means that the effect of the cause is to enable the speaker to translate.

"His face became red."

This one looks easy, doesn't it? But I put it in to illustrate again how Trarsani accomplishes with particles what English does with prepositions and helper verbs. How would you handle this, since the Trarsani don't see the need for a verb meaning become?

We know that at some point in time his face wasn't red, and that sometime later, it is. Therefore, we have a relationship with time, so we might suspect an aspect is involved. Indeed, if we go over the list again, we see that applying the inchoative aspect doo- to a stative verb (like to be red) means that the subject is entering that state. So we have it. We add the simple past tense po- because it sounds like it happened sometime in the past.

"Beesh na-pro po-doo-irai."

Or transliterated, "Face of-him did-begin-is-red."

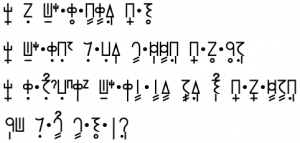

And just to remind you that there actually is a Trarsani alphabet, which we've slighted here, I'll document these four sentences in their proper script. At first glance, it almost looks like Egyptian hieroglyphs.

I think that's where I'll stop it for this installment. I was originally planning to include case and voice as well as some unusual, distinctly Trarsani, particles, but now I'm thinking that's too much for one sitting and will therefore make it Part 5 and push everything else back one.

When I made up the structure for Trarsani, I thought it was quite logical, more so, actually, than English, that the interpreter requires less advance knowledge of varied sentence structures, that there are fewer bizarre and contradictory constructions, that someone could learn it from scratch much easier. I still believe all of that. However, I've also come to realize just how different it is from English and how difficult it can be to explain everything to an English speaker. A linguist who has studied such varied languages as Turkish, Mandarin, and Twi, will probably pick up on everything quickly. Not so Joe Blow. For that, I apologize. I have a lot of experience teaching, but none teaching languages.

It also makes me aware of just how intelligent Nekalee is to have been able to pick up English so rapidly. Yes, we know Nekalee is a genius, but we don't know from A Hierarchy of Gods that her I.Q. on the human scale is well above 200. Well, we know now.

Comments

There are no comments for this post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.