2012

Aug

16

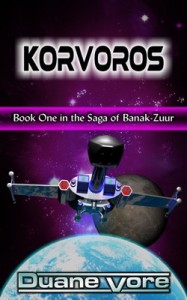

Korvoros

Recently revised and enhanced!

141,000 words.

Content advisory: Language, sexual situations, space-battle violence.

Upstairs, in the middle of the night, a green glow penetrates 19-year-old Timothy Sauger's bedroom window. Downstairs, something enters through the patio doors. By morning, he is on his way to an alien society 59 light-years from Earth. His anticipated escape from boredom fulfills its promise more spectacularly than he had planned.

Circumstances arranged before his birth plunge him immediately into mysteries older than human civilization, and a race for his life against pirates that are more than pirates and cryptic forces that are more than forces. Accompanied by Wendy Miller, the only other living human to know of the Free Space Alliance, he embarks on a desperate journey across half the galaxy, delving into puzzles that were old when Neanderthals roamed the earth. They struggle to stay a step ahead of a terrifying, lingering consciousness that is pushing him forward into the Dead Zone, from where no one returns.

There is scant consolation in knowing that those things — or beings — he fears are themselves afraid of something even older and more mysterious. Can he find the bravery within himself and discover the missing links from the foggiest past before it is too late to save himself, his new friends, and the Alliance? Can he halt the formidable new threat that has appeared? And how is he himself connected to it all?

The deepest darkness and master of enigmas has only a name: Korvoros

The opening of chapter 1

Daybreak

DKTR-118573-2 plugged himself into his control room terminal and slammed in his toggles. It was going to be a damned rough ride.

He had spent the last 127 million kilometers in tight space with all systems off, even the meteorite deflectors, as he streaked toward that small blue planet. When he had emerged from the Dead Zone, there had been virtually no power left to embrace his survival; his copper reserves were long depleted. He had been tapping the rarefaction field for two light-years, and it was now gone, having left just enough energy to deflect his course toward the nearest planet with any sort of industry. A low charge remained in the accumulators, but this was only to be measured in milliseconds of full-power drive even if he'd had copper vapor.

For one brief fraction of a second, he energized the short-range scanners. One ephemeral glimpse of the universe — a still photograph stored in the ship's memory banks — provided all the information he needed for final calculations.

Time to impact with Earth's atmosphere: 933 seconds. Velocity of impact: 52.8 kilometers per second. Minimum deflector power to keep the ship from melting: 152.7 megawatts. His energy would be gone at about 2100 meters above sea level, at a velocity of still over two kilometers per second. The landing was going to be a hell of a lot rougher than the ride.

But there were still some things he could do, all of which he had planned earlier. He opened the forward and midsection airlocks, first the inner doors, then deliberately overriding the safety interlocks, the outers. There was no outrush of air: ever since he had left the Dead Zone and realized the seriousness of his situation, he had conserved every unit of energy available. And with no organic life on board anymore, maintaining the environment would be a waste. Then he opened all the cargo doors and service hatches. At least he would not be trapped inside.

He accessed the encephalotron. "Enter following into log. Archival storage."

"Acknowledged," the machine replied. "Activating storage classes 3 and 4."

"Date 5422.0109. I am now approaching Earth, known technically as 6744-03. Being in the Dark Zone, I will not be be detected. I will be forced to make a landing with insufficient energy to avert the destruction of this speedster. Should any parts of this vessel or of myself be recovered, please return personally to Rosh Dyrrya in care of Dyrrya Industrial, Arcora. Or, failing this, please contact Winslow John Miller, Berkeley, California, Earth. The recovery of these archival records may be essential to the survival of civilization in this part of the galaxy. This is DKTR-118573-2, colloquially known as 'Two,' signing off. Last entry into log. End of file.

"Now," he directed. "Translate the entire log of this voyage into English and Kria-Ki, converting units as applicable. Keep the original Hamon, and record these onto archival media as well."

"Acknowledged."

That final entry, he knew, was probably futile; if he were destroyed in the crash, local authorities would not be able to break the vault's stasis field anyway. The time to impact was just under twelve minutes; there was little to do now but wait.

The ship struck the tenuous outer layers of Earth's atmosphere just as any meteor would have done. A gentle swaying was the only observable detail to indicate this fact to either Two or the encephalotron, but it meant keeping an eye on skin temperature. Air friction at 53 kilometers per second was serious stuff, too much for mere metal to tolerate very long. Already the nose was heating. Two waited until the last moment before its shear strength would be compromised, then cut in the forward meteorite deflectors.

The invisible protective umbrella flashed on to vanguard the ship. But even that shield could not prevent the atoms of the atmosphere from being ionized into incandescence as they dissipated the ship's kinetic energy, nor could they hide the miles-long trail of glowing matter behind him. Oh, well. So much for being discreet.

Inside, the acceleration mounted as the ship dropped into the ever-increasing density of the atmosphere. The deflector radiators strained at their anchors, sending shrieks of protest through the structural frame of the speedster. But Two had already computed those forces; the anchors would hold. So would the radiators and so would the ship.

Seconds passed. The spaceship slowed. The incandescence faded. Two monitored his energy reserves. When the accumulators reached nearly zero, the ship was, just as had been calculated, about 2000 meters above the forest canopy below, and traveling nearly that far every second.

The vessel had served its purpose; now was time to abandon ship. He activated the encephalotron vault's stasis field with the last few megajoules, then threw himself out of his terminal, down the corridor and through the midsection airlock into the brisk winter air, his armored top turned to face still-dangerous blast of passing atmosphere. He adjusted his photoreceptors to accommodate the dazzling sunlight, and lashed out tractor and pressor beams to brake his descent before the remaining air friction damaged something. The torpedo-shaped craft that had served him so well had left him far behind. Two watched woefully. His only contact with civilization was soaring to its destruction in the mountains that dotted the horizon.

From his viewpoint, without magnification, it disappeared in a cloud of dust on the face of a cliff. But Two knew that the impact was a good 25 kilometers away and that the dust was really chunks of flying rock larger then he was. Seconds later the sound arrived. It reverberated like the crash of nearby thunder. There wasn't a cloud in the sky.

He reached the site in a few more minutes, having lowered his velocity and altitude to reasonable values. The impact had scarred the mountain with a miniature crater and ugly radiating fracture lines. It was still hot. Fragments of metal and rock were tumbling down the slopes below, melting snow, setting fires among the beds of pine needles if they hesitated in one place too long, and sending up bursts of steam as they dropped into the creek at the bottom. The encephalotron vault as well as large pieces of the ship lay in the water, but Two could not guess what pieces they might have been. The vault was still enclosed within the mirror boundary of its stasis field; at least that much had survived. Without it, he might not be able to get home.

This planet had very little in the way of serviceable technology, but they did have phased array radar; he had detected their signals on his last scan. He could have been optimistic enough to think the local officials would have missed a 200-meter-long structure of titanium alloy plowing through the atmosphere at 53 kilometers per second and leaving in its wake a concussion wave that would shatter windows for miles, but he considered himself a realist. Computers would have plotted the trajectory and determined the point of landfall. Two did not know how much time the authorities would leave him before they arrived, but he was certain they would not be generous.

He had to have this mess cleaned up by then.

Comments

There are no comments for this post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.